Our Story

HOCKEY’S OLDEST BUSINESS – SINCE 1847

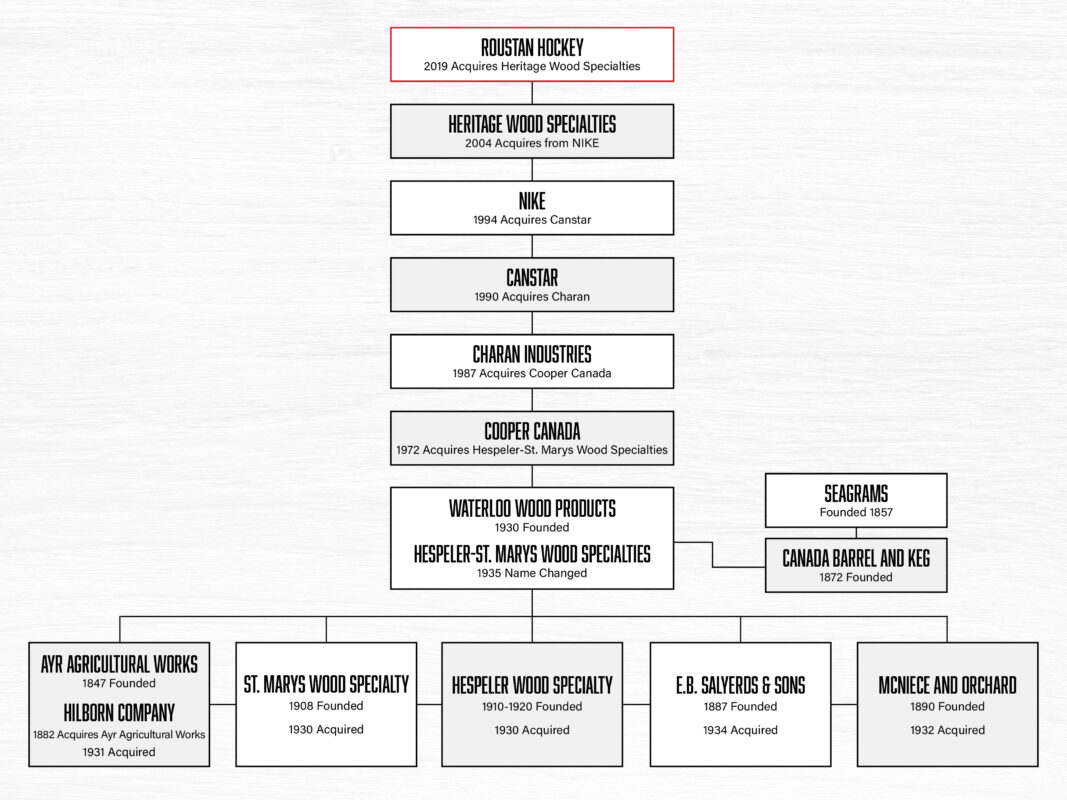

Stick-making factories have been around for the better part of two centuries in Canada. Roustan Hockey’s is 175 years in the making. Here’s its full story.

BY ADAM PROTEAU

PHOTO CREDIT: AYR NEWS

When you’re talking about the beginnings of the hockey stick industry, you have to start in Ayr, Ontario. Situated on the Nith River, south and west respectively of the larger cities of Kitchener and Cambridge, the southwestern Ontario town originated in 1824 with an initial population of 230 people.

The territory in the area, eventually known as the North Dumfries township, consisted of 94,305 acres. It was initially sold in 1798 by Six Nations Mohawk military and political leader Joseph Brant to Philip Stedman for the price of £8,841. Steadman died in 1801, and his sister, Mrs. John Sparksman, sold the land to Thomas William Clarke; in 1816 Clarke sold the property to wealthy Scottish immigrant William Dickson. The price of the land was now £24,000.

Ayr originally was a group of three settlements – Jedburgh to the east, Nithvale to the west, and Mudge’s Mills in the center – that eventually was amalgamated into one town. Ayr’s first settler was Abel Mudge – the namesake of Mudge’s Mills – who built a dam, grist mill and sawmill. Virtually all settlers who followed Mudge were Scottish tradesmen, farmers, and artisans.

The entire area began to flourish. Jedburgh was founded by another Scotsman, John Hall, in 1832. Hall built a distillery and a flour mill that same year. Nithvale, meanwhile, had a flour mill and two sawmills. Mudge’s Mill was founded in 1839 by initial settlers James Jackson, J.R. Andrews and Robert Wylie. The name “Ayr” first appeared in 1840, when it was assigned to the local post office; it was given that name by Wylie, who was inspired by the name of his hometown of Ayr, Scotland.

Interestingly enough, William Rillie, the grandfather of W. Graeme Roustan, the current owner of the company that dates back to 1847 in Ayr, Ontario – now the last hockey stick manufacturer in Canada – was born in Ayr, Scotland in 1899. (Roustan is also the owner and publisher of The Hockey News.)

Business in Ayr quickly began to grow across a number of industries. Smith’s Canadian Gazetteer’s 1846 edition describes Ayr as the home of two churches, a post office receiving mail once a week, a fulling mill and carding machine, a tannery, a blacksmith, two shoemakers, a pair of tailors, a grist mill, two carpenters and one maker and one cooper and a repairer of barrels and casks. But the biggest business in Ayr, for many decades, was a foundry that casted metal.

One year later, in 1847, the foundation for what would turn out to be the last surviving Canadian hockey stick-making company was laid down in Ayr. The company which began as the Ayr Agricultural Works, founded by John Watson, located at the intersection of Piper Street and Church Street. At that time it was making farm implements, including mowing, threshing and reaping tools, as well as plow handles, straw cutters, reapers and stoves.

Also happening in 1847, Alexander Graham Bell was born, a telegraph line between Quebec and London, Ontario went live, the St. Lawrence Canal was finished and the Irish Potato Famine caused 100,000 of its citizens to flee Ireland and immigrate to what was then called British North America, the province of Canada and specifically Upper Canada. Influenza, measles and typhoid disease were running rampant throughout the province of Canada, which caused tens of thousands of deaths.

In 1850, Ayr had a town hall and a fire department. At that point, the population had grown to 700, and the city had its own library, newspaper, and a large furniture factory. Increased demand helped create a whopping five flour mills, as well as a woolen mill.

Fifteen years after it opened, Watson’s company was shipping agricultural implements across Canada. Infrastructure in and around Ayr also evolved and improved: a road to the relatively close town of Galt, Ontario, had been built, as had a railway. Exportable goods were delivered by ox cart to the train station in Paris, Ontario.

In 1879, Ayr got its own rail line from the Credit Valley Railway. In 1882, John Watson’s Ayr Agricultural Works was purchased by William Hilborn, who changed the name of the company to the Hilborn Company. And as fate would have it, Hilborn, who was born in Waterloo, Ontario, on December 1, 1848, was a fan of the flourishing sport of hockey, and by 1889, the factory had 40 employees.

In 1884, Jedburgh, Mudge’s Mills and Nithvale were absorbed into Ayr when the village was incorporated and John Watson was the town’s first Reeve. Only one year prior to that, Ayr’s streets were lit with coal oil lamps. By 1901, Ayr had concrete sidewalks. And soon after the turn of the century, the Hilborn Company, and Ayr itself, were at a crossroads.

Ayr’s population suffered a decline by 1910, with some people relocating to nearby Preston, Ontario and Berlin, Ontario. In the same era, hockey began to blossom as Canada’s pastime. Prior to the Hilborn Company’s venture into stick-making, hockey participants had to make their own sticks. People would cut down a hickory or alder piece of wood, carve three-foot sections, and file the piece into a hockey stick shape. Initial sticks looked more like field-hockey sticks and eventually, stick blades became longer and more square, extending the shaft of the stick longer and allowing players to play the game in a more upright body position. But Hilborn would soon change the landscape.

Hilborn’s interest in hockey came in no small part from a family perspective. His sons, William Jr. and Albert Hilborn, would go on in 1896-97 to play in and win a Toronto Bank League and City championship, which was the forerunner of the National Hockey League, but it also came out of a business necessity. Indeed, when the Hilborn Company’s farm business lagged, William Hilborn turned his attention to the fledgling sport. Hilborn came to realize his machine that shaped and molded plow handles also could create hockey sticks. In fact, just one piece of rock elm wood could generate eight sticks for sale.

The Hilborn Company wasn’t the only hockey stick manufacturer; as rival company E.B. Salyerds & Sons Ltd. first put a stick they called the “Salyerds Special Hockey Stick” on the market in 1887. By 1910, the Hilborn Company had established a robust market of its own, with sales of thousands of dozens of sticks, and a business that was now employing hockey stick salesmen. As of 1912, a dozen Hilborn hockey sticks would cost you $1. Hilborn was also one of the first stick manufacturers to make special, exclusive orders for NHL players.

Ten years later, in 1920, the Hilborn Company had grown to the point it was supplying sticks and baseball bats to elite sports manufacturers and sellers across the country, including Spalding, C.C.M., and the Eaton’s Canadian department store chain. Yet there was still a functional flaw in the sticks themselves as each stick was still made from one piece of lumber, which increased the weight of the stick and made the thin stick blades easy to split.

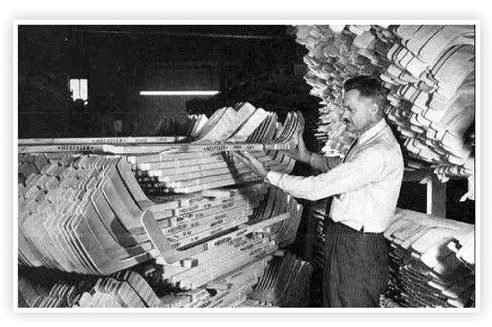

In 1928, Hilborn produced the first spliced skater’s stick, which allowed them to use other hardwoods, as rock elm had become a scarce commodity by that time. The revolutionary stick also had separate pieces for the blade and shaft, and the general public responded very positively to the changes. As a result, the factory in Ayr was thriving, moving as many as 300 sticks through each employee’s hands every day. Factory workers at the Hilborn plant in Ayr had a six-day-a-week, 10-hours-a-day schedule, and were paid 30 cents an hour.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression hit the Hilborn Company hard, and the company was sold to Waterloo Wood Products Limited on February 13, 1931, for $25,000 – just $1,000 more than Hilborn had bought it for in 1882. The sale in 1931 was part of a bigger conglomeration movement that eventually would merge five hockey stick-making companies into Waterloo Wood Products, but the Hilborn Company in Ayr was the very first, and very best at what it did.

As the hockey stick industry flourished in southwestern Ontario, one of the final big hockey stick making companies came to be. This was the St. Marys Wood Specialty Company, which was incorporated on March 30, 1908. It was located in St. Marys, Ontario, on the banks of the Thames River, some 22 miles from London, Ontario. St. Marys was initially settled in 1839, by Thomas Ingersoll, the brother of famous Canadian War of 1812 heroine Laura Secord who built a mill at Little Falls, Ontario, for the Canada Company, a British land development business.

Two years after Ingersoll’s first building in St. Marys, he built a grist mill and sawmill in return for 337 acres of land in the area. Before long, other businesses, including a carriage maker, a flax mill, a cheese maker and a blacksmith popped up, and the building of Grand Trunk railways from 1857-1860 spurred development in the lumber and limestone quarry industries. In the riverbed and the banks of the Thames River, limestone was at or near the surface, and could be quarried for building materials. The first library in the city opened in 1857, and in 1904, a grant from the Andrew Carnegie Foundation paved the way for a freestanding library building. The village of St. Marys was incorporated in 1864, and by 1913, the library was home to some 4,000 books. But the region’s connection to limestone gave St. Marys its nickname of “Stonetown”.

By 1866, the mercantile industry in St. Marys flourished, with Beattie’s General Store leading the pack. Another local retailer, Timothy Eaton, picked up his business and relocated it to Toronto, where it would come to be known as one of Canada’s all-time most successful retailers.

As of 1905, 51-year-old businessman Solen Lewis Doolittle, a native of Aylmer, Ontario, set up shop in St. Marys. By 1907, his intent was to create a hockey stick and handle factory, and he asked the Town Council to provide him with a $6,000 loan. As a result, the St. Marys Wood Specialty Company was incorporated on March 30, 1908. The business quickly moved forward, and on June 25, 1908, the St. Marys Wood Specialty Company was opened, at a site on James Street, just north of the local flax mill.

Just one year after that, the St. Marys Wood Specialty Company plant was moving at breakneck speed, producing a full line of hockey sticks and baseball bats. There were 27 models of baseball bats, and 16 different types of hockey sticks. A price list in 1909 displayed sticks for defensemen, forwards, and goalies, and in boys, junior and miniature styles. Prices ranged from 45 cents per dozen sticks to $4.05 per dozen for goalie sticks. By 1910, the St. Marys Wood Specialty Company was selling sticks as far away as Regina, Saskatchewan and it also manufactured ax, pick and hammer handles.

Unfortunately, a major fire destroyed the St. Marys stick factory on January 24, 1912. That put a halt to production, but Doolittle didn’t waste time getting his business back on track. By August of that same year, they shifted operations to the flax mill, and by early 1913, they were up and running again. The baseball bats were made of straight-grained, air-seasoned, second-growth white ash, and they were sold through a network of businesses in Ottawa, Ontario; Winnipeg, Manitoba; Montreal, Quebec; and St. John’s, New Brunswick.

Business for Doolittle in St. Marys continued to prosper. By 1917, St. Marys Wood Specialty Company was the largest stick-making factory in the world. The company developed the first pinned blade hockey stick, and in 1922, it patented the first three-piece stick with a tapered blade. On the baseball front, St. Marys Wood Specialty Company sold bats in crates of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and one-dozen. The best-selling models were sold at $10.00 per dozen. The exhaust of the stick-and-bat-making factory came via a 250-horsepower engine with a 10-tonne flywheel that powered most of the plant’s machinery. Steam for the engine came from a boiler that burned scrap wood and sawdust, and the boiler produced sufficient steam to keep the factory warm in winter and heat its wood-drying kilns.

There was change at the top of St. Marys Wood Specialty Company after Doolittle died at age 65 from pneumonia on October 25, 1919. However, the plant continued operating, even throughout The Great Depression. The St. Marys Wood Specialty Company employed dozens of people over the years, often through generations of the same families. One employee, Russell “Buster” Seaton, worked there for 55 years, and two of his sons, as well as two of his grandsons, also went on to be employees of the company. St. Marys Wood Specialty Company also hired a local woman, Grace Crozier, as a young girl, and she worked there for more than 25 years before retiring as head of the baseball bats line in 1972. This was prior to the gender equality movement, and Crozier stood out as a symbol of progress for the region and the business in particular.

On November 30, 1930, St. Marys Wood Specialty Company was sold to Waterloo Wood Products Limited for $28,000.

The Waterloo Chronicle published on its front page of the November 27, 1930 newspaper the headline; “New Waterloo Company is Incorporated.” In the story they report that “Manager Leo Henhoeffer of the Canada Barrels and Kegs Limited stated the incorporation of this company (Waterloo Wood Products Limited) did not mean another manufacturing concern for Waterloo.” Essentially, Canada Barrels and Kegs had simply created a division in which to house its future acquisition plans of existing hockey stick manufacturing companies. A simple entity search through the Province of Ontario’s website confirms that Waterloo Wood Products Limited was incorporated on November 3, 1930, 24 days before it was front page news in Waterloo.

On July 12, 1933, the entire St. Marys Wood Specialty Company, including the employees, were moved from St. Marys to Hespeler, Ontario. All St. Marys Wood Specialty Company employees, machinery and operations would eventually be transferred to Hespeler, Ontario, to the Hespeler Wood Specialties, Ltd. factory that Waterloo Wood Products Limited had also acquired in 1930. And the new, bigger company would quickly endear itself to Hespeler citizens. One resident, who played in the Hespeler Minor Hockey League, remembers the plant having a separate rack with hockey stick seconds that Hespeler children could buy at a discounted price. Another area resident, Dave Cressman, described the unique experience that came when his father took him to the plant to buy a Hespeler Mic Mac brand stick for 50 cents.

On January 7, 1935, the Waterloo Wood Products Limited company officially changed its name to Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties Ltd., combining the names from its two first acquisitions, Hespeler Wood Specialties Ltd. and St. Mary Wood Specialty Company as part of a larger conglomerate business move. Additional acquisitions also included the Hilborn Company of Ayr, Ontario, E.B. Salyerds & Sons Ltd. of Preston, Ontario, and McNiece and Orchard Ltd. of Montreal, Quebec.

All five hockey stick-making factories were closed, except for the Hespeler plant. In short order, all competition for hockey stick manufacturers was essentially gone, and at the same time, the sport of hockey eventually began churning out elite players in the St. Marys area. In 1956, the Ontario Hockey Association’s Junior ‘B’ League team, the St. Marys Lincolns, was founded, and the team went on to produce NHL talents, including J.P. Parise, Bob Boughner, Terry Crisp, Mark Bell, Steve Shields and Don Luce. Meanwhile, St. Marys eventually became the home of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1994.

As for the hockey stick business, three years after the name change of the business and the merger of the five companies – and after increasing the price of sticks by approximately 30 percent – Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties Ltd. was regarded as the world’s largest hockey stick manufacturer. And for the following 34 years, Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties Ltd. dominated the industry, before it was sold to Cooper Canada Ltd. on July 5, 1972.

The town of Hespeler, Ontario, which is now a neighborhood in the northeastern part of the city of Cambridge, Ontario, did not start off as the center of the hockey-stick-making business in North America it eventually became. Hespeler, located in the Grand River Valley along the Speed River, was in its early days the territory of an Iroquois people regarded by their neighbors as “Attawandaron,” which is translated to mean “people who speak differently.”

In the early 1600s. French explorers of the area called the Attawandaron “Neutrals,” because they maintained peace with their Huron and Iroquois neighbors. Halfway through the 17th century, the “Neutral” territory was conquered by the invading Iroquois during the Beaver Wars. In 1784, the Grand River Valley was officially granted by the British Crown to the Loyalist Iroquois group led by the famous Mohawk and military leader Theyendanegea or Joseph Brant.

The County of Brant in Ontario is named after Joseph Brant and encompasses the City of Brantford, which is where the current home of the 1847 Ayr Agricultural Works (Roustan Hockey) calls home today after moving from Hespeler in 2019.

The region that became to be known as Hespeler was purchased in 1798 by a group of Pennsylvania Mennonites from the Six Nations Indians, with the help of developer and pioneer western merchant Richard Beasley. The area had its first settler in 1809, Abraham Clemens, who purchased 515 acres of land from Beasley. One year later, 40-year-old Cornelius Pannabecker, a blacksmith from Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, and the son of a Mennonite minister, moved to the town and soon set up shop. In 1830, 43-year-old Joseph Olberholtzer, also the son of a Pennsylvania Mennonite preacher, purchased a far larger area of land that would first be known as Bergeytown named after resident Michael Bergey before it changed its name to New Hope in 1835.

In 1845, German fur trader Jacob Hespeler arrived in the region, buying a 145-acre tract on the Speed River. He initially built an industrial complex that was the genesis of Hespeler’s eventual industrialization, which soon would consist of textile and woolen mills. As of 1846, its population was only 100 people, but there was a grist and saw mill, a tavern, a pail factory, two tailors and two blacksmiths, a tannery, and a pair of shoemakers. When the railway arrived in 1859, businesses benefited and the population had grown to the point Hespeler was incorporated as a village.

In 1869, Hespeler’s population had grown to 1,200, and major manufacturers settled into the community, including a knitting mill and woolens factory. By 1901, there were enough people and businesses within Hespeler to qualify it as an incorporated town.

Continued growth allowed Hespeler to gain a reputation as a business enclave. It got another boost in 1911, when the electric railway system between nearby Galt, Ontario, and Preston, Ontario, reached Hespeler and what would later be known as Kitchener, Ontario. However, a massive part of Hespeler’s legacy began in 1921, when the Hespeler Wood Specialty Company was founded by Zachariah Hall. Zachariah Adam Hall was born in Millbank, Canada West in 1865 and died in Guelph, Ontario in 1952 having served as the MPP for Waterloo South in the provincial government as a Conservative.

Hall and Oscar Zyrd acquired the Parkin Elevator Co. Ltd. building on Sheffield Street in Hespeler in 1910 after that company had gone bankrupt. Then they acquired the Dominion Heating and Ventilating Co. buildings across the street some years later, turning them into a pattern building and machine shop for raw materials including wood. It was in those two buildings at 63 Sheffield Street in Hespeler that their Hespeler Wood Specialty Company would begin in 1921.

In 1922, at which time the Hespeler plant – located on Sheffield St. in the business center of Hespeler, and employing approximately 25 people – patented the “Supreme” three-piece goaltender stick. In 1925, it registered two patents for two-piece players’ sticks. In 1926, they produced four patents for heel joints, one of which turned out to be the forerunner of the modern heel-jointed stick.

In August of 1930, the Hespeler Wood Specialty Co. was bought by Waterloo Wood Products Limited, a subsidiary of Canada Barrel and Keg, owned by the famous Joseph E. Seagram and Sons Ltd. It was its first purchase of a hockey stick company, and it paid the biggest price – $85,000 – of any of the five companies Canada Barrel and Keg would end up buying. And its inventiveness continued.

First, there was the “tie buster” heel-jointed stick in 1932. One year later, they produced the “Mic Mac” stick, the “Red Flash” stick, and many others. Hespeler also produced spliced sticks in 1926, 1927, and 1933. Although the Great Depression hurt them, the Hespeler Wood Specialty pushed through, and in 1935, they changed the name of the company to Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialty Ltd. By that point, they were producing 20 different hockey sticks, 10 high-grade hickory, ax and sledge handles, and 29 baseball bat models. The baseball bats cost $3.00 apiece, and they had distribution across Canada, as far as Vancouver.

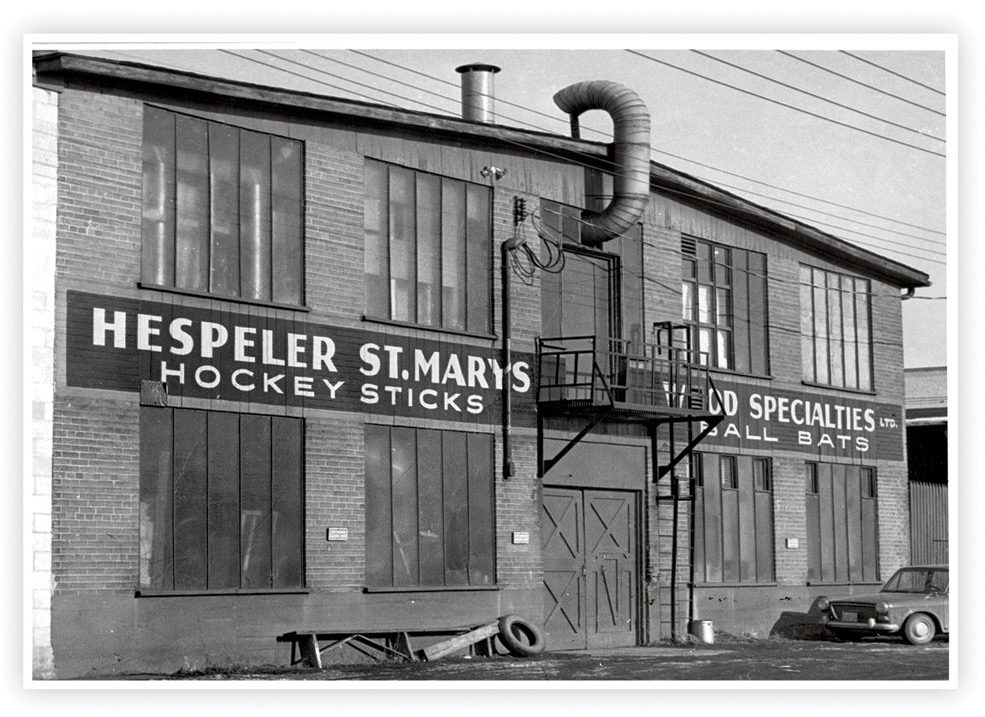

But make no mistake – Hespeler was not only on the map of the hockey-stick-making industry, it was the center of the business. All of the amalgamated companies were closed by the new ownership except for the Hespeler plant. It would continue on to be successful for decades. Sticks were made in Hespeler at 65 Sheffield Street until December 31, 2021 when it relocated to Brantford, Ontario after being sold to W. Graeme Roustan in 2019. Long before that sale and transfer to a bigger city, the community of Hespeler was forever associated with the stick-making business.

Canada was not the only nation that had a flourishing hockey-stick-making industry operating in the late 19th-century. The United States also had a stick-making business or, at least, the arm of a stick-making business that served a growing hockey community, and that business was E.B. Salyerds & Sons Ltd.

The company was named for founder Edward Burgess Salyerds, who in 1862 was born in Preston, Ontario which amalgamated in 1973 along with Hespeler and Galt as Cambridge, Ontario. When he was just 14 years old, Salyerds began making brushes, and in 1887, he took advantage of the skyrocketing increase in interest in hockey by putting out the “Salyerds Special Hockey Stick”, the first of its kind in the marketplace. Its popularity laid the foundation for the “E.B. Salyerds & Sons Ltd.” business, and Salyerds’ Canadian factory, which at that point was making brushes and sticks in Preston was thriving.

Salyerds decision to expand to the United States directly benefited Avoca, New York, a village southeast of Buffalo, when a stick-making plant was constructed there. Avoca was first settled in 1794, prior to which, it was occupied by Seneca Indians. The town itself was founded and comprised four smaller towns (Bath, Cohocton, Howard, and Wheeler) in 1843. Avoca is approximately 36.3 square miles in size, and the Cohocton River runs through it. In 2010, the U.S. census identified its population at 2,264.

Back in 1901, Salyerds posted an advertisement in The Galt (Ontario) Reporter. The ad read, “E.B. Salyerds Preston, Ontario. Manufacturers of The Salyerds Hockey Sticks. They are made of rock elm and are the best on the market.” By 1908, Salyerds factory in Preston – two stories in height, made of brick, and located on the corners of Water and Hamilton Streets – and Avoca were cranking out very popular stick brands, including Midget, and “Kiddo” sticks, and at least 17 employees were working in the Preston plant.

E.B. Salyerds died in 1935 and was buried in his hometown of Preston, but one year earlier, on July 9, 1934, E.B. Salyerds & Sons Ltd. was sold to conglomerate business Waterloo Wood Products Limited for $40,000. At that price, it was the second-most-lucrative hockey stick-maker on the planet, and the sole hockey-stick-maker to have operations in both Canada and America. Waterloo Wood Products Limited, which purchased five hockey-stick-making businesses in total in a four-year period, closed the two E.B. Salyerds plants and consolidated operations in Hespeler, Ontario. Salyerds’ employees, and its plant manager, relocated to Hespeler to work at the sole remaining plant.

The Salyerds stick-making company wasn’t the biggest of its kind, but its transnational growth was crucial to the development of the sport in northern New York and the United States in general. Like the stick-makers that had come before it, Salyerds did not start out as a stick-making business, but ultimately, Salyerds became at least as famous for its sticks than anything else it ever made. And hockey fans in America and Canada paid considerable money to purchase its products.

The last major hockey-stick-making manufacturer in the earliest days of the industry was Montreal based McNiece and Orchard Ltd. The company started in 1890 after McNiece patriarch Ozie McNiece made the sticks for he and his Montreal Crystal teammates when they won the 1887 ACHA championship. Situated at 774 St. Catherine Street West in Montreal, McNiece and Orchard was an athletic outfitter that also had a location in Rouses Point, New York, (a small city in the northernmost part of New York State, and a city named for a famous French-Canadian soldier who fought on the same side as Americans in their war of independence).

On the American side, Rouses Point was an incorporated village as of 1877, and the population of the area came in at approximately 2,000 as of 1892. Being in the frontlines of a cross-border operation gave McNiece and Orchard great opportunity, but they weren’t only a retail, mud-and-brick-stores brand, also selling their wares via a catalog component of the business.

In 1915, for example, the McNiece and Orchard annual catalog sold “Extra Special” hockey sticks, and had in it a picture of the 1912-13 Quebec Bulldogs, a team that would twice win the Stanley Cup in the National Hockey Association, the precursor league to the NHL with the straightforward advertising caption, “This club uses our goods.” But that wasn’t the only championship team that McNiece and Orchard made sticks for. The 1898 Montreal Victorias, the 1900 Montreal Shamrocks and the 1906 Montreal Wanderers. Stars of the day that used McNiece and Orchard sticks included legendary goalie Georges Vezina, “Newsy” Lalonde, Sprague Cleghorn, Lester Patrick, and Frank McGee.

McNiece and Orchard continued to thrive in the early turn of the 20th century, to the point they were a supplier of sticks for the Montreal Canadiens for decades. They had ingenuity as well. For instance, in 1914 they were the creators of the modern, paddle-style goaltender’s stick. And iconic early NHL star Eddie Shore used their sticks. They made a name for their business by selling sticks, usually for $1.00 apiece. They were especially proud of their NHL connection, and they would often make customized sticks if you were willing to pay enough for it. Thousands of Eastern-region Canadians, as well as New Yorkers, saw McNiece and Orchard as a sports status symbol.

That said, they also suffered through the Great Depression, so when Waterloo Wood Products Limited – came calling to purchase McNiece and Orchard on September 15, 1932, there was no fight amongst the company’s longtime owners to keep it. McNiece and Orchard sold for $13,000, the smallest amount of any of the five stick-making companies purchased by Waterloo Wood Products Limited, but it gave them a competitive advantage in the Quebec and New York marketplaces. Like three of the other four locations, its factory ceased operations and its skilled labor relocated to Hespeler, Ontario, where the business remained until 2022, when it moved to Brantford, Ontario.

In 1857, William Hespeler, a merchant from present day Kitchener (then called Berlin until 1916), Ontario, and George Randall formed the Granite Mills and Waterloo Distillery in Waterloo (then called Western Canada until 1867), Ontario. In 1864, Joseph Emm Seagram was hired by Hespeler to oversee his interest in the company.

By 1883, Seagram had bought out all of the owners and then changed the name of the company to Joseph Seagram Flour Mill and Distillery Company. In 1911, in order to establish that his sons were the future of the company, he changed the name of the company one more time to Joseph E. Seagram and Sons Ltd. Edward became president and took the reins of the company when Joseph died in 1919.

Also in Waterloo in 1872, Mueller Cooperage was founded by Karl Mueller on the corner at Regina and Erb streets. In 1906, after a new factory was built, his son John Charles Mueller took over and in 1914 he changed the name to Charles Mueller Cooperage. In 1920, the business was sold to Canada Barrels and Kegs Limited after it had been newly incorporated in Ontario on September 30, 1920, by its parent company, Joseph E. Seagram and Sons Ltd.

After Joseph E. Seagram died in 1919, Samuel Bronfman and his brothers in 1923 purchased Greenbrier Distillery in the United States, took it apart piece by piece and shipped it all to LaSalle, Quebec, where their company, Distillers Corporation Limited reassembled and opened the distillery.

In 1928, the Bronfman’s Distillers Corporation Limited of Montreal purchased the Joseph E. Seagram and Sons Ltd. company from its heir Edward F. Seagram. From 1928 forward, it was Samuel Bronfman who was in charge of Joseph E. Seagram and Sons Ltd. and its related entities, Canada Barrels and Kegs, Limited and Waterloo Wood Products, Limited.

Once the five major hockey stick-making companies were acquired by what was known at the time as Waterloo Wood Products Limited by 1934, focus on the growth of the business zeroed in on a centralized production plant in Hespeler, Ontario.

Situated on Sheffield Street, the stick-making plant took advantage of Hespeler’s growing population, which was placed at 1,200 ten years after its inception as a village in 1589. And it also would go on to produce world-class baseball bats that would be used by major league baseball stars Tony Fernandez, Paul Molitor, Joe Carter, and Tim Raines at its facility.

The Hespeler plant came to be regarded as what the city was regarded for: well-made hockey sticks and baseball bats. And it did sufficient business to please the Waterloo Wood Products owners.

One of the five stick-making companies that Waterloo Wood Products acquired, the St. Marys Wood Specialty Company, was located southwest of Stratford, Ontario, not far from Hespeler, and many employees relocated to Hespeler after it was acquired in 1930.

Once they arrived in their new workplace, the former St. Marys Wood Specialty employees who had become new Waterloo Wood Products employees were impressed by the production capabilities they had seen at the Hespeler factory.

There was a huge exhaust plume located on the top of the factory, a sign that massive amounts of energy were being used. Wayne Fischer, president of the Ontario Steam Heritage Museum, told the Waterloo Region Record in 2020 that the plant had to generate power for itself to run the machines, and the exhaust was the result of a 250 horsepower steam engine with a 10 ton flywheel. Steam was necessary to drive the engine, and it came from a boiler that worked on burned scrap wood and sawdust. Right now, it sits in the Ontario Steam Heritage Museum, in nearby Puslinch, Ontario, where it is in the process of being restored to its original working condition.

Not long after Waterloo Wood Products took over the five Ontario stick-making companies, it changed its name again. The date of the change was January 7, 1935, and the new name of the business was “Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties Ltd.” Immediately, the newly-named company continued to churn out elite-quality sticks and bats. One of those sticks was used by iconic Montreal Canadiens superstar center Howie Morenz. It lasted throughout the decades and although it did not have any knob on the upper end when a hockey fanatic put it up for sale in 2017, it still had its original tape blade. And it generated much interest. Vintage sticks have been known to sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars; for instance, a handmade stick, carved out of one piece of sugar maple wood between 1835-1838 was purchased for $300,000 in 2015.

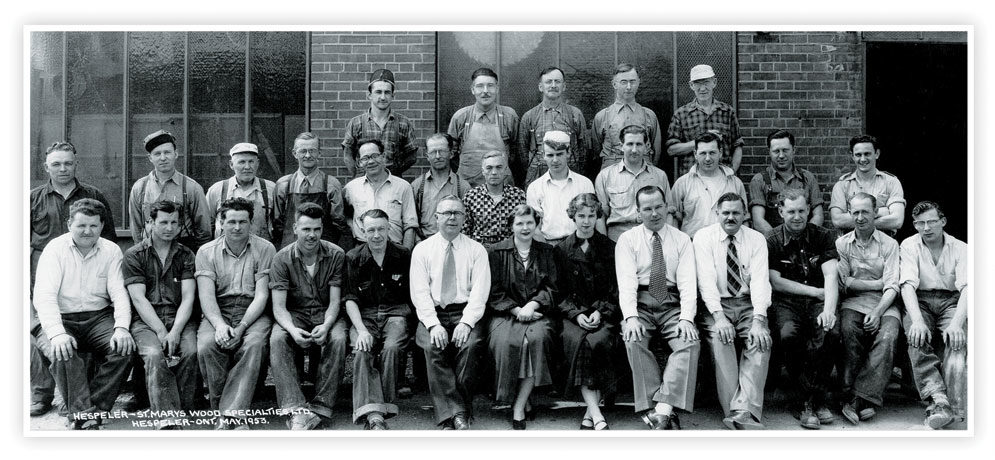

For the 36-and-a-half years that followed the company’s name change, Hespeler-St. Marys would lead the stick-making industry. It also offered job opportunities for women such as office manager Doris Krueger who worked in her position at Hespeler-St. Marys from 1944-1974. Other employees of the company served for decades and some for nearly a half-century in their roles. Working there was a family affair for multiple generations. On occasion, sticks were produced under other names for major manufacturers such as Spalding, and for the Canada-wide-famous Eaton’s catalog. And as the years passed, the strength of the Hespeler-St. Marys brand only grew.

The different sticks branded as “Green Flash”, “Blue Flash” and “Mic-Mac” were huge commercial successes for Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties, Ltd.

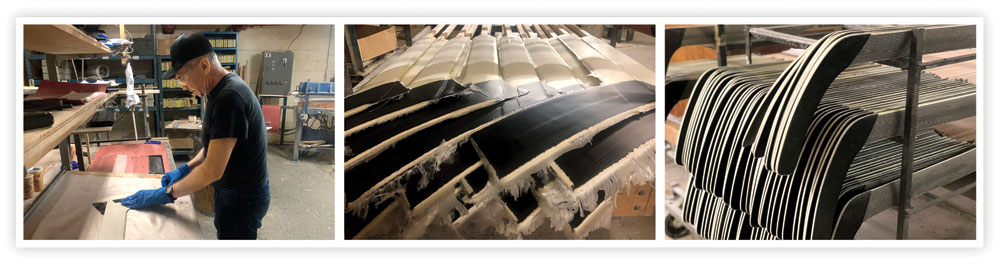

The evolution of the hockey stick also continued during the Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties era. Where original models of sticks were one-piece models, with blades carved from the roots of trees, NHL players who used them wanted more flexibility in their sticks. Two-piece and three-piece models soon arrived and a mortise joint held the stick blade in place. In addition, industrial glues were used to bond the heel of the stick.

The Hespeler-St. Marys brand was the best-seller up until the 1960s, when it was challenged by Quebec stick-makers Sher-Wood and Victoriaville. Hespeler-St.-Marys advertised itself as “The World’s Oldest Hockey Stick Manufacturers,” but competition cut into their financial bottom line.

After the death of Samuel Bronfman on July 10, 1971, his son Edgar Bronfman took over the Seagram business as its new President.

Samuel and his brother Allan in 1951 created two holding companies for their children, Cemp Investments for Samuels children and Edper Investments for Allan’s. Upon Samuels death, these two entities would get assets which included Seco Ltd. which held the stock of Distillers-Seagram Ltd.

Ten years later in 1961, the holding company that Samuel named Cemp Investments after his four children, Charles Bronfman, Edgar Bronfman, Aileen “Minda” Bronfman de Gunzburg and Phyllis Lambert would buy out Edper leaving the Montreal branch of the Bronfman family as the sole owner.

In 1987, Charles Bronfman announced that Cemp was being dissolved and the net assets were being shared among the four siblings. Charles’ son and Samuels’s grandson Stephen Bronfman is based in Montreal and is the CEO of Claridge, a private equity firm. Stephen hired Pierre Boivin in 2011 to be its CEO after having been the CEO of the Montreal Canadiens from 1999 to 2011. Boivin was coincidently the CEO of Canstar when it was sold to NIKE in 1994.

Less than a year after Samuels death in 1971, on July 5, 1972, Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties Ltd. was sold to Cooper of Canada Limited. The Seagrams and Bronfman ownership era had come to an end.

Prior to its foray into the stick-making business, the Cooper company, under the name Cooper Weeks, an amalgamation of its founders’ names, Jack Cooper and Cecil Weeks. The company had earned its place in the market by making ski and snowshoe harness sets, as well as hockey shin guards and gloves. In 1969, they introduced the plastic hockey stick replacement blade to the market, mainly for use in road hockey games.

After Jack Cooper bought out his partner, he renamed the company on June 15, 1971, Cooper Canada. He had much bigger aspirations for its line of hockey products, aspirations that would carry it at the top of the industry for nearly 15 years as both it and the rest of the business was branching out across the planet.

In its heyday, the two decades between 1960 and 1980, Cooper Canada was Canada’s leading manufacturer of hockey and lacrosse equipment, as well as baseball gloves. In the approximate middle of that span, it took over as the main maker of hockey sticks, but before we get to that point, let’s take time to detail Cooper’s evolution as a company.

The genesis of the eventual Cooper brand began in 1905, when Scottish-Canadian businessman R.H. Cameron, founded General Leather Goods. His nephew, Cecil John Weeks, began working with him, and in 1949, Weeks and another key figure, Jack Cooper who joined the General Leather Goods company of 15 people in 1932 and partnered up to purchase the company from Cameron.

Prior to that change in ownership, the company made its name building ski and snowshoe harnesses, and during the Great Depression, it began making hockey shin guards in 1933 and hockey gloves in 1935. After the sale, the business was rebranded “Cooper Weeks,” and the business expanded dramatically, while building its credibility through a working relationship with members of the professional hockey community. In the 1950s and early 1960s, Cooper Weeks joined forces with Frank Selke, then the manager of the Montreal Canadiens, to lighten the weight and improve the safety and durability of hockey equipment, and in 1969, Cooper Weeks introduced the first plastic hockey stick replacement blade used primarily in road hockey.

As it grew, Cooper Weeks continued to branch out into new areas of the hockey industry. Cooper worked with its customers to lead the way in areas such as goaltenders’ throat protection and pro lacrosse equipment. It was a pioneer of sorts in the 1970s when it worked with athletes, including former NHL goalie Dave Dryden, brother of net-minding icon Ken Dryden, to make the best possible protective equipment for players.

As a widely supported business, Cooper Weeks attracted significant corporate attention, and in the early 1970s, a massive change took place when Cecil Weeks sold his share of the business to John Cooper. On June 17, 1971, Cooper Weeks was renamed “Cooper Canada.” And, a little more than one year later, Cooper purchased hockey stick and baseball bat-maker Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties Ltd. from the Seagram company, which had owned the business for more than 37 years.

For the following 15 years, Cooper, based in Toronto, flourished as the primary hockey stick-making company in North America. And although many of its products were the gold standard for the stick-making business, Cooper’s willingness to try new things blew up in its face on one particular product: they were called “Cooperalls,” and they were a streamlined hockey pant and girdle that became trendy, in some areas, at least, before a backlash came about.

The flashy Cooperalls first were used in the Ontario Hockey League in the late 1970s and then were tested by a handful of NHL teams, including the Winnipeg Jets and Quebec Nordiques, in their training camp workouts. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, CCM, the hockey rival of Cooper, paid tribute by putting out its own style of long pants and girdle, one that was used in two NHL seasons by the Philadelphia Flyers (1981-83) and in one season by the Hartford Whalers (1982-83). The Cooperalls design did not have any lasting power in hockey, but it did gain traction in Canadian ringette and broomball, and those sports continue to utilize that brand and design today.

While the hockey stick arm of the company continued to thrive, Cooper Canada got a huge boost on March 27, 1986, when Major League Baseball approved Cooper bats for use in their game, making them the first Canadian manufacturer of bats to get that green light. Eventually, Hespeler, Ontario, made Cooper bats that were used by many baseball stars, including Tim Raines, Paul Molitor, Joe Carter, Hubie Brooks, Tony Fernandez, Kelly Gruber, Cecil Fielder and Jesse Barfield. Cooper’s Hespeler factory pushed its production capabilities to give them a 30 percent market share of baseball bat sales by 1988, second only to the “Louisville Slugger” brand.

However, on May 13, 1987, Cooper Canada was purchased by Montreal-based Charan Industries for approximately $36 million. One year earlier, Cooper claimed a profit of $1.4 million based on sales of $80.5 million. Charan, which also made toys and stationery prior to acquiring Cooper, claimed $6 million in profit that same year on sales of $75 million. Although Jack Cooper’s time running the stick-and-equipment leviathan was at an end decades after it began, his impact on the business was huge, and in 1989, he was honored with admission into the Canadian Business Hall of Fame.

Charan Industries survived for two decades before dissolving on March 1, 2000. But well before that, back in February of 1990, Charan sold its Cooper brand to Canstar Inc., the parent company of Bauer Hockey. At that point, Canstar’s stable of brands included Bauer, Lange, Mega, Daoust and Micron skates, as well as Cooper and Flak equipment and Bauer inline skates. Canstar bragged that about 70 percent of NHLers wore one brand of Canstar skates or another. And within five years of purchasing the company from Cooper, Canstar sold all hockey assets of Cooper Canada to global sporting goods giant Nike Inc. for approximately $395 million.

Nike paid Canstar $19.875 for each share in the business, some 60 percent higher than the market price. In 1994, the year of its sale, Canstar projected its hockey-business sales to be in the area of $205 million, a 41 percent boost from 1993. That said, Nike was already doing mammoth business across the planet, earning some $43.9 billion in a single year prior to the sale. The hockey side of the business was important, but it wasn’t what Nike was banking on to keep it at the forefront of the industry.

Indeed, less than a decade after it was sold by Canstar, the hockey arm of Nike would undergo two name changes, and in 2004, they sold off what was Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties Limited to a group of five Nike employees who in 2019 then sold it to W. Graeme Roustan. Nike would then sell off the remaining Bauer and Cooper assets in 2008 to W. Graeme Roustan and his partner at a tumultuous time for the sport and the hockey equipment-making industry in general.

As the hockey stick-making business moved into the modern age, arguably the planet’s biggest sports apparel and equipment maker, Nike Inc., decided to buy into the market in a massive way. In December of 1994, Nike purchased the hockey assets of Cooper Canada (via parent company Canstar) for approximately $395 million. That may sound like a huge sum of money, but considering Nike had made approximately $43.9 billion in the year before the purchase of Cooper, it was a relatively small investment. Cooper had projected its 1994 hockey sales to be $205 million, so the investment wasn’t going to be repaid right away, but Nike believed it was acquiring a brand in Bauer that would only improve its global footprint.

When Nike announced the purchase, the Beaverton, Oregon-based company revealed Canstar would become a wholly-owned subsidiary of Nike, but it would keep its separate identities. And Canstar was an attractive investment in part because of its wide array of products. At the time of Nike’s acquisition, Canstar had more than 1,700 hockey items for sale. In addition to sticks, it sold hockey skates under the Bauer, Daoust, Lange, Mega and Micron brand names; it made hockey protective equipment under the Cooper and Flak brands. It sold skate blades under the ICM, John Wilson and Tuuk brands and it made in-line roller skates and protective gear under the Bauer brand. At the time of the sale to Nike, more than 70 percent of NHL players were wearing Canstar-branded skates. In four years of operating the hockey businesses, Canstar had developed a strong distribution system in North America, but Nike’s reach aimed to extend it through Europe and bolster the brands across the planet.

That said, once it did take over the Canstar/Cooper businesses, Nike quickly learned the hockey stick-and-equipment industry was like all businesses, in that it was not guaranteed a profit.

Still, at the time Nike purchased Canstar/Cooper, Nike C.E.O. Phil Knight was quoted as saying he believed hockey was North America’s fourth-most culturally-significant sport, and he wanted Nike to capitalize, in part, on the growth of inline hockey. However, the financial waters for Nike in the hockey business became choppy enough for them that it triggered their exit from it one decade after it purchased Canstar.

Two years after that purchase, in June of 1996, the name of Nike’s hockey division was changed to Bauer Inc. Two years subsequent to that name change, in December of 1998, a new business was formed: Bauer Nike Hockey Inc. was the new name of the company that took the place of Canstar’s hockey properties. The famous stick-making plant in Hespeler continued churning out sticks, but the flatlining of growth in the rollerblade business hurt Nike’s bottom line, and the hockey business did not approach the $1 billion plateau some industry analysts had forecasted it would. A change in strategy would be necessary in a relatively short period of time.

Indeed, prices were relatively high for many products, a strategy that some hockey equipment executives accurately projected would limit the overall hockey market and keep it as a niche sport. To wit, in April of 1997, Nike ice skates appeared on the market at prices ranging from $220-425. (Some 10 years later, Nike’s premium skates were selling for $750 per pair.) In the same era, a pair of padded nylon hockey pants went for $170. Synthetic gloves retailed for $120-170. And hockey sticks, now composed of materials ranging from aircraft aluminum to graphite and bullet-proof Kevlar, sold for between $40-100. It was not at all cheap for families to fund their hockey dreams.

Meanwhile, the popularity of in-line skating dropped from 32 million participants in 1998 to 17 million six years later. Competition on the hockey side was fierce and varied, and cost-cutting and contraction became part of Nike’s business plan with the hockey division. The firm’s skate and helmet plant in St. Jerome, Quebec, just north of Montreal, was downsized in three phases, and they moved production to Asia. And in 2003, Nike Bauer announced it would be shuttering its stick-making factory in Hespeler the following year. However, it proved to be a brief closure.

In a matter of weeks, in June of 2004, a new era began for the old Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties Limited Hespeler plant. It was the first time that a group of the plant’s longtime employees stepped up, formed a new business named Heritage Wood Specialties Inc., and bought out the hockey stick-making plant.

With the businesses that remained under Nike’s umbrella, Nike Bauer would outsource roughly 90 percent of its production to other makers in Asia. From 2002 to 2008, its chief competitor, Reebok-CCM, closed five plants in Quebec and Ontario, outsourcing manufacturing to other countries, eliminating some 600 jobs. The Easton and Warrior hockey companies outsourced part of their manufacturing to Asia and retained their factories in Mexico. The retraction in the business was only growing. And in the post-Nike-ownership era, the stick-making employees had to put up their own money as well as borrow funds from Canadian investor Mark Fackoury to keep the business in Hespeler afloat.

Meanwhile, in 2008, four years after Heritage Wood Specialties Inc. was formed, Montreal native and fervent hockey fan W. Graeme Roustan along with a partner purchased the remainder of Nike’s hockey division for approximately $200 million and he became its new Chairman. That was less than half of what Nike paid for it. But there was already a sense the overall stick-making market was pushing toward a “last-man standing” scenario in Canada and the USA, with one company eventually taking over more or less the entire hockey stick manufacturing business, and Roustan recognized that direction and saw an opportunity for a rebound and a return to growth for the industry.

And Nike, which wanted to get out of the manufacturing elements of the business in order to focus on growth industries with the highest financial returns, no longer had the willingness to continue taking on the challenges. It eventually found in Roustan, the best person who would shepherd Bauer in 2008 and beyond just as a handful of the Hespeler factory’s longtime employees eventually did in 2009 with Roustan.

In 2004, as it fought to persevere in the hockey stick-making industry, the Hespeler hockey stick plant – now owned by five former Nike employees backed by Canadian investor (and Hespeler-area local) Mark Fackoury – took the new name of Hespeler Wood Specialties Inc. (HWSI) in June of 2004. And the new company quickly looked to take a bigger stake in the hockey business overall. Fackoury loaned large sums of money into purchasing extremely expensive equipment from as far away as Finland, and they did purchase a plant in Finland and another in Quebec.

In 2009, the HWSI employee-ownership group were seeking out a chief financial officer with a track record of great success, and they found one in Curtis Clairmont, a veteran businessman who had thrived in high-level management as an executive at well-known convenience store chain 7-11 and former video rental goliath Blockbuster Video. Clairmont initially was hired as a consultant for HWSI in 2009 after one of the former Nike employees had sold his shares to Fackoury, but he quickly became the man entrusted with the business side of things, so that Fackoury, a very hands-off owner, and the four remaining former Nike employees could go back to what they did best.

Clairmont knew the challenges facing HWSI were serious and potentially dire. One person told him the wooden hockey stick was “going the way of the wooden tennis racket,” in other words, it was going to be extinct but he was still focused on finding a way to make the business work. And after a couple of weeks, the Kitchener-Waterloo native, a Cornell University goalie who idolized Ken Dryden in his younger days, told HWSI ownership there was indeed a business opportunity for them, but it had to be as a “last man standing” type scenario.

In that regard, the idea was for them to put their collective nose to the grindstone, and outlast their competitors. But Clairmont did not like the decision to buy the plants in Finland and Quebec. The fact that there wasn’t a guarantee of sale of sticks from Bauer, or anyone else, to purchase products from those plants was a major sticking point for Clairmont, and both the Quebec and Finnish companies were bleeding money.

As Clairmont saw it, the hockey-stick making companies dictated demand by limiting supply, an odd situation, as normally it’s consumers who dictate demand. And, in short order, he bristled at what he saw, which was that Bauer and CCM were pushing consumer demand toward their outsourced composite stick businesses. That wasn’t to HWSI’s benefit, and that was a problem that could’ve killed the Hespeler plant. So, one of Clairmont’s first moves was to sell off and close the Quebec plant, and sell off the Finland plant. They lost money on those transactions, but from Clairmont’s position, they were starting HWSI anew again, with no major debts to address. It was a fresh start.

Next up was modernizing their technologies. For example, Clairmont had to have designed and built a wraparound graphics machine, so an employee went to China, and HWSI got sufficient financial support to have the machine custom made. Another thing they were lacking in was modern graphics; they were still living in the old school world of screen art. And most, if not all HWSI employees had a dearth of experience in corporate management. Thus, many changes took place in the eight years Clairmont was steering the ship financially.

Under Clairmont’s stewardship, HWSI forged new partnerships, including one with famous brand Easton. More importantly, Clairmont had developed a customized cost process to the stick-making business, and transparency was brought to an industry that, prior to then, had very little of it. They persuaded Easton they were a better partner than Quebec-based rival Industries ACM, and they got Easton’s business.

Early on in Clairmont’s tenure with HWSI, he was dealing with financial losses, but with the Easton business acquisition, HWSI was profitable but not terribly so, but making money was a crucial turn-the-corner moment for Fackoury and the four employee-owners.

However, Clairmont noticed a disturbing trend. The influence that Bauer and CCM had on the costs and availability of most hockey-related equipment, including hockey sticks. In the early days of composite stick-making, you could pay upwards of $200 for a single stick and the big hockey equipment producers were rapidly taking lower margin wood and fiberglass sticks off the market altogether. Mark-ups on hockey sticks, for instance, were obscene. If you made a $50 hockey stick, you sold it for five times that amount. In the short-term, that was great for the manufacturer’s bottom line. But if you were looking at the macro picture, the long-term picture, you could see you were making hockey into an elitist game, and that there was going to be no long-term growth for the sport.

This was not a good harbinger of what could’ve been to come for HWSI.

On the other hand, HWSI’s competitors, slowly-but-surely, were falling by the wayside. Easton was one of the biggest names to go under, but they hardly were alone. Quebec-based Industries ACM also would go bankrupt in 2016, and Clairmont persuaded Fackoury to purchase ACM’s assets. That “last man standing” approach Clairmont had envisioned was becoming more and more of a reality for HWSI.

There were also not going to be any start-up companies to rival HWSI. When you have to pay $300,000 for a molder that did nothing other than adding a corner radius to a hockey stick, you know you’re dealing with an industry that requires massive amounts of capital for any given business to outlast its competitors, and thus, we see fewer competitors.

In 2017, Clairmont told Fackoury that HWSI had arrived at a crossroads of sorts. The company needed to invest large amounts of capital to either modernize the Hespeler plant that was built in the early 1900s or build a new factory altogether. The Hespeler factory had become a decrepit building with holes so big in its roof that it had sunshine on sunny days, rain on rainy days and snow on snowy days coming through the roof of the plant. When the facility’s elevator broke down, production ground to a complete halt, as the finishing process for sticks would be done on the second floor of the building. It was time to either move, sell or close the stick-making business.

Nobody questioned it was high time for a new stick-making plant and at that point, Claremont presented the options. Fackoury and the four former Nike employees decided it was time to sell HWSI. And the name that came up prominently was venture capitalist, past Chairman and part owner of Bauer from 2008 to 2012 and devoted hockey fan W. Graeme Roustan.

The Montreal Canadiens fan and finalist in the 2009 bidding process for the Montreal Canadiens and devotee of the sport had purchased The Hockey News in 2018, the Christian and Northland brands of hockey sticks two years sooner. By buying The Hockey News, Christian, Northland and now, HWSI, Roustan was positioning himself to have a media brand and an advertising platform as well as a hockey stick manufacturing base for his owned hockey brands. It was a fully-integrated vertical strategy, and all it needed to make Roustan’s vision for the business complete was a new factory in Canada.

Soon enough, HWSI, with one more name change to Roustan Hockey in 2019, would get its new factory in 2022 located in Brantford, Ontario. And the best for the business was yet to come.

Through its history of more than 175 years dating back to 1847, the company’s heritage dates back to twenty years before Canada became a country in 1867. The business has made hockey sticks in Ontario, Quebec, the USA and Finland. It has experienced many highs and lows and survived the Great Depression, a massive fire, and two World Wars.

From the time where five separate companies flourished in the mid-19th-century, right up until today, the resilience of the Hespeler plant has been its most defining feature. There have been many ownership and name changes to the company, but the goal remained the same: generating high-quality hockey sticks, for use both at the professional and amateur levels of the sport.

The owner who would shepherd the company into the next century, W. Graeme Roustan, had a very good idea of where he could take the business when he acquired it in 2019.

Roustan made his initial mark in the business world with successes in the finance, aviation, manufacturing, consumer products and sports and entertainment industries. The Montreal native is a noted philanthropist and avowed hockey fan, and he has experience with the hockey business dating back to his time in 2008 as chairman of the board and purchaser of Nike/Bauer. Roustan left Bauer in 2012 after he took the company public on the Toronto Stock Exchange as its Chairman. Since then, he has continued to acquire hockey companies. He’s been a prominent supporter of the Canadian Women’s Hockey League throughout its existence and is a key mover and shaker behind the scenes of the hockey world as well as a member of the Canadian Olympic Committee.

Few hockey figures have worked in more elements of the sport than Roustan, and whenever he saw an opportunity arise that would allow him to get more invested in the sport as a whole, Roustan never hesitated to step up and acquire more hockey businesses.

Indeed, when the Christian and Northland hockey equipment company came up for sale in 2016, Roustan moved quickly to purchase it. Two years later, The Hockey News came up for sale, and Roustan again swooped in and bought the famous magazine and brand. Then, in 2019, when the Hespeler-based Hespeler Wood Specialties Inc. (HWSI) business went on sale, Roustan again put his money where his mouth was and added it to his growing number of hockey businesses. By buying The Hockey News, Christian, Northland and HWSI, Roustan was positioning himself to have a media brand and an advertising platform as well as a manufacturing base for hockey sticks. It was a fully-integrated vertical strategy, and all it needed to make Roustan’s vision for the business complete was a brand new factory in Canada.

The first order of business was to change its name to better reflect the hockey businesses that will become a part of its future story. Heritage Wood Specialties became Roustan Hockey.

The Hespeler plant was world-famous for its storied history, but the reality was the plant itself was no longer safe and usable. Now known as “Roustan Hockey,” HWSI needed a new home, and Roustan found it in a location in Brantford, Ontario, the birthplace of all-time hockey icon Wayne Gretzky – and Gretzky’s late father, Walter, who was a frequent visitor to the old plant – and a city that wasn’t all that far from Hespeler and just down the street from Ayr where it all started in 1847, 175 years earlier.

In 2020, Roustan invested millions of dollars in the brand-new factory, which was 65,000 square feet – twice the size of the Hespeler factory that the business had been housed in since 1921. Then, in 2022, Roustan Hockey Ltd. purchased Scarborough, Ontario’s McKenney Custom Sports, a custom hockey and lacrosse equipment manufacturer that mostly made goaltender equipment. Once again, Roustan cornered the market on an element of the game that needed the corporate support and holistic view of the hockey industry that he provided where nobody else could.

From 1921 through 2021, the Hespeler plant, along with the other plants that were part of Hespeler-St. Marys Wood Specialties Ltd. factories manufactured more than 100 million hockey sticks for hockey players. But there was no question it was time for a different direction, and keeping jobs in Canada was crucial for Roustan. He achieved that goal by moving operations to Brantford. He’d realized the company’s goal of being the “last man standing” in the marketplace, and as a result, a new era for the stick-making industry had begun.

Most of the Hespeler plant’s longtime employees – including many of the experienced employees who had helped purchase the plant to keep stick-making jobs in Canada in the early 2000s – followed their job movement to Brantford, and local politicians heartily welcomed the company and its employees to their new community.

There remain challenges for the stick-making business in Canada, but everyone involved with Roustan Hockey felt the new energy and renewed purpose Roustan brought to the table. And by the end of 2021, the move to Brantford was complete. A new era had arrived for Roustan Hockey, and although the plant had to be relocated to continue on, the alternative of shutting down the company was never a proper solution for Roustan. He believed in Canada’s love affair with the sport and put his funds behind any available business that touched Canadians the way hockey does.

Ultimately, Roustan accurately recognized the direction the hockey industry must head towards, which is to repatriate some manufacturing from overseas, and he saw numerous opportunities for a financial rebound and a return to growth. In 2022, Canadian Tire Corporation, who shares Roustan’s vision for “Made in Canada”’ hockey sticks and for the preservation of Canadian manufacturing jobs repatriated all of the Sherwood brand sticks that Roustan can make from overseas manufacturers.

From 1847, when Canada was just a colony of the United Kingdom, to the present day, hockey stick manufacturing has been in continuous business operations for more than 175 years. From Ayr Agricultural Works in 1847 to today, more than 100 million sticks have been manufactured with sales of more than $1 billion during this 175-year span which makes Roustan Hockey, hockey’s oldest business and success story.

– with files from Brian Logie

First image photo credit: Ayr News